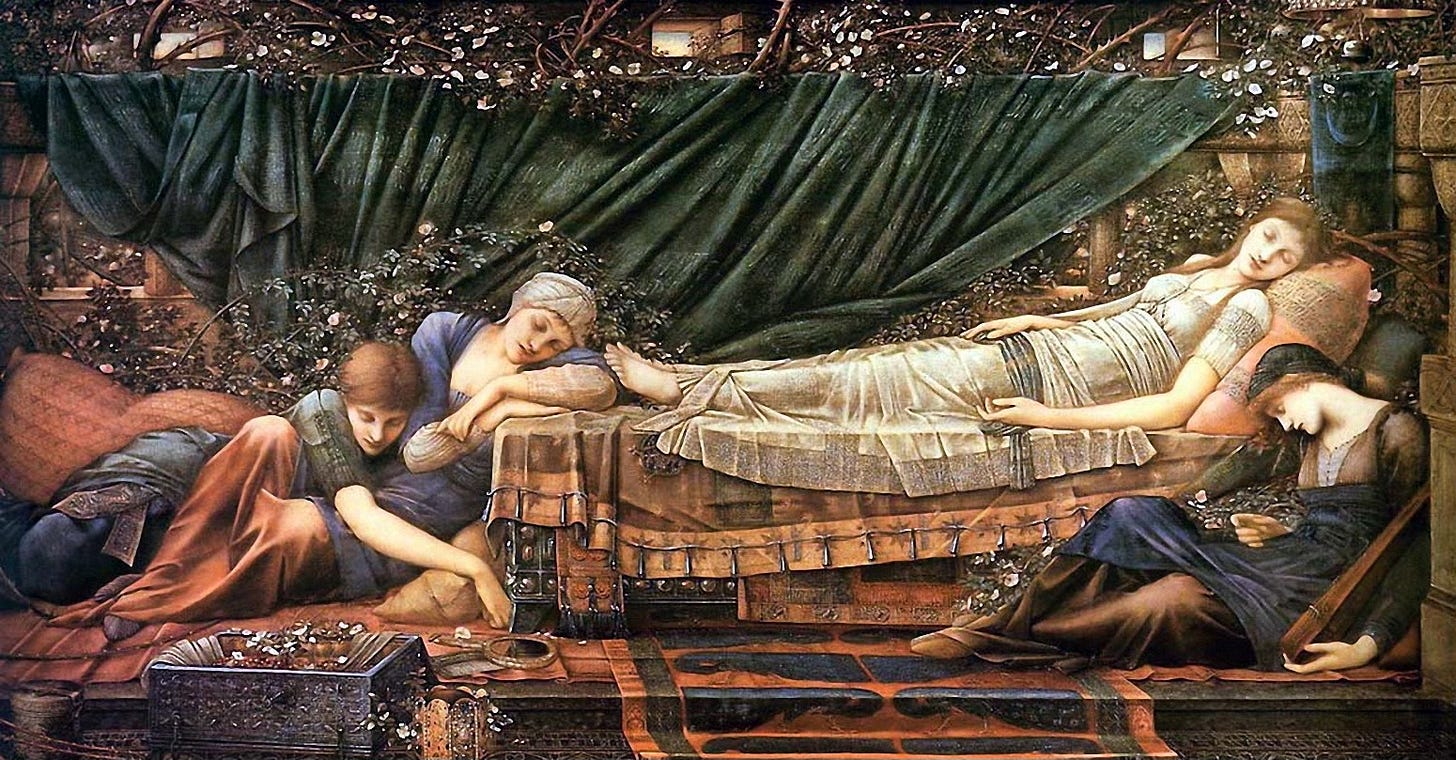

“You would have thought her an angel, so fair was she to behold. The trance had not taken away the lovely color of her complexion. Her cheeks were delicately flushed, her lips like coral. Her eyes, indeed, were closed, but her gentle breathing could be heard, and it was therefore plain that she was not dead. The king commanded that she should be left to sleep in peace until the hour of her awakening should come.”

From The Sleeping Beauty In the Wood by Charles Perrault, 1695

“’A man’s secrets are his own, monsieur…’, retorted the prisoner. ‘and not at the mercy of just anyone’”

From The Man in The Iron Mask by Alexander Dumas, 1847

*Note to the reader: This piece covers some difficult topics and might be upsetting to read for those who have experienced trauma or known someone who has attempted or committed suicide.

In the fall of 1991, early in my second year of anesthesiology residency in Seattle, I was desperately looking forward to my upcoming month-long intensive care unit rotation. I was tired of being in the operating room, exhausted and burnt out by the seemingly endless year-long litany of one surgical case after another. I was especially tired of working inside windowless rooms day after day, and every third night. The first year of anesthesia residency is hard and relentless. After coming off a particularly brutal stretch of work, I craved a break from the OR.

Little did I know that my month in the ICU would challenge me in ways that I could only have imagined, leaving me wondering whether I had the emotional intelligence, grit and maturity to continue pursuing my goal of becoming a competent physician and anesthesiologist. Even after nearly thirty-five years, a lifetime in medicine, I still regret how poorly I was prepared to deal with the heartbreak of traumatic illness, or even worse, the death of a patient. The early childhood loss of my father could have helped me be more compassionate and more empathetic towards others. But it didn’t. Even twenty years after that personal tragedy, it was still a fresh wound far from being scarred over. With hindsight and the maturity, and wisdom gained from a long career in medicine, only now do I understand that my own grief at that young age was still far too raw and unresolved. As a result, I selfishly held my emotions in check to protect myself. Empathy is the key to healing, not only for oneself, but for others.

I remember most a young teenage girl who was a passenger in a high-speed, head-on, auto collision that ultimately robbed her of her precious, evanescent life. She spent her last days intubated, on a ventilator in the ICU. I cared for her slowly dying body but was poorly prepared and unable to care for her grief-stricken parents by giving them the few words of comfort, compassion and hope that they so desperately craved. They refused to accept the truth of her condition and were intransigent and stubborn in their belief in a miracle that would never come. I was the cold realist, delivering a harsh and graceless message of facts and statistics. In their grief they took shelter in anger, and blamed her condition on me, the messenger. I wish I could say that I understood this reaction, or sought help understanding it from my ICU fellow, or my attending, or one of the many mental health professionals on staff…or even a pastor. But I didn’t. And as I internalized their anger, I became angry in return, losing sight of what mattered most, empathy.

During that same month, I was the resident assigned to care for a fifteen-year-old boy, who in some inexplicable dark moment in his young life had decided to just end it. Attempting suicide, he managed to position the barrel of a shotgun just under his chin, pushing the cold steel into the soft skin just behind his jawbone. Maybe he used his toe to pull the trigger, or he rigged it so he could fire it with a stick? He must have given it some thought, but clearly not enough. When he fired, the shotgun kicked forward. He survived the blast of buckshot, but blew off his jaw, his tongue, his nose, eyes and forehead, leaving him without a face. Speechless, sightless and grotesque, his brain, and dark suicidal thoughts remained intact.

I spent nearly a month with him, debriding the dead tissue from what was left of his face, managing his fluid intake, his electrolyte levels and his antibiotics. But I was unable to give him emotional comfort, or help his sad, solitary wordless mother. She sat far from his bed in the dark corner of the room, barely acknowledging me, or I her. It was not that I was incapable of kindness, but I simply did not have the maturity or the life experience to know what to say. So, I worked, in near silence, inches from him, pretending, or desperately wishing that he could not hear me, while I tried to repair his body but not his mind.

I vividly remember these two young souls, whose lives, and those of their family and everyone who worked with them were marred by tragedy. Their short time on this earth intersected with mine at such an influential point in my training and development as a physician. So, I need to tell their stories and remember them, for who they were and for the lives they touched and for teaching me how to be a better person.

I am watching television in the break room, glued to the spectacle of the Clarence Thomas Supreme Court nomination hearing, listening to Anita Hill being mercilessly and rudely grilled by one white patrician member of the Senate Judiciary Committee after another. My pager goes off. I look down and see the numbers – 911- followed by the code for the helicopter transport trauma bay in the ER. I take off on a run to the emergency room and arrive in time to see a gurney being wheeled inside surrounded by Air Northwest trauma nurses and ER physicians. The patient is a young woman who was just airlifted from the scene of a high-speed head on traffic accident somewhere east of Snoqualmie pass. I overhear that she was the front seat passenger, and that the driver was pronounced dead at the scene. The girl is strapped to a backboard under a silver metallic blanket, already intubated in the field and being bag ventilated by a medic at the top of the bed. I notice her long blond hair cascading on either side of the red pads holding her head in place.

In the first year of anesthesia residency, the work is constant and unyielding. I typically set out for the hospital every morning before the first light of dawn, when most people are still sanely asleep and comfortable in their warm beds. Seattle was a particularly tough place for me to live, due to its northern latitude and climate. Despite my east-coast childhood, having moved to California and spending the prior eleven years in Palo Alto and Santa Cruz, I had become used to warmer and sunnier weather. As a new anesthesia resident, this meant not seeing the sun for days at a stretch. Natives of this perpetually overcast and rain-misted city, accustomed to the grey overcast and the short days would always chide me asking, “What did you expect? You’re inside anyway.” This didn’t make me feel better. The unfortunate fact is that the quality of light is different in the operating room – it’s unnatural, and there is no way of knowing what is going on outdoors. Being outside, or even looking out a window on gloomy, cloudy and rainy days is far less depressing than weeks in a row spent going from one case to another in the bright, windowless, fluorescently lit operating room. Like a Las Vegas casino, there is no way to know what is going on in the outside world.

As spring turned to summer, I became a second-year resident and as the weeks ticked by to September, I felt ready for something different. Fortunately, it’s common at this point in training to take a hiatus from surgical anesthesia and complete a few of the required out-of-the-OR rotations. First up was a month in the intensive care unit. While I knew this would be a challenge of a different sort, it was somewhat familiar to me having spent time there as a medical student and then again as an internal medicine intern. This time, however, I had the benefit of a whole year of residency under my belt and had vastly expanded my knowledge and improved my manual skills, such as the ability to effortlessly intubate airways and slickly place arterial and central venous catheters. Aside from my experience and confidence, I was looking forward to the predictability that twelve-hour shift work offered, even though some of these shifts were overnight.

And there were windows!

Although I would still be inside, I could gaze out the windows at the impossibly blue late summer sky and the magnificent snowy peak of Mt. Rainier whose massive, crisp white, iconic profile causes residents of Seattle to joyfully exclaim, “The Mountain is out!”

Once she is inside and in the trauma bay, there is not much for me to do but watch as the trauma team efficiently executes their well-practiced dance, draws labs, places additional large bore intravenous lines, and performs a quick very old-school peritoneal lavage looking for internal bleeding – a liter of saline solution is freely infused into the abdominal cavity via a 10 gauge IV inserted through the umbilicus and then gravity drained back into the bag. We are taught that if you can read a newspaper through the IV tubing, there is a low likelihood of internal hemorrhage. Some resident places a radial arterial line to transduce blood pressure and obtain arterial blood for a blood gas. The respiratory therapist measures the depth of the endotracheal tube and secures it with a head strap and holder, and the patient gets initial C-spine X-rays and then is quickly taken to the CT scanner as soon her vitals are stabilized.

I began my ICU rotation in early September at Harborview hospital in Seattle. After a short drive from my house in the Madrona neighborhood to an unmetered all-day parking spot in an alley near Terry Street - a closely guarded secret spot passed from resident to resident. I strode up First Hill, arriving at the main doors of the hospital. Dawn was breaking in the East, and I stopped briefly to enjoy the sunrise. I thought to myself that I had a whole month of early fall days before the dark and rain set in to enjoy the warm morning sunlight falling on my face, so I paused for a few precious minutes that morning to let it soak in. It felt incredible.

Over a century old, Harborview is the King County public hospital and Washington’s only Level 1 trauma center and burn unit. There are big university hospitals and small community ones, private for-profit, hospitals or budget stretched county and public medical centers. Harborview is a mix of the above. Because it is affiliated with the University of Washington, it is a major teaching and research center. It is also a public county hospital tasked with serving the poor and the underinsured of the Seattle area. Patients arrive constantly - on foot, by paramedics and via Life-Flight air ambulance from all over the state of Washington, Alaska, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming.

Walking into an unfamiliar hospital or on a new ward on the first day of a clinical rotation always elicited in me a combination of excitement mixed with a healthy dose of nervous dread. By this point in my training, I was used to it, but this rotation was different. It was the first time in my residency that I would be working outside of the confines of Virginia Mason, a large city hospital and medical center, but a small training program compared to the University of Washington. I would now be part of a much larger team composed of medical students, interns, residents and fellows from both my program as well as from UW and would have to prove myself worthy once again.

I had chosen Virginia Mason in the residency match as my first choice over the other programs where I interviewed, including Stanford, Harvard Mass General and Beth Israel, Yale, Johns Hopkins and Penn. I picked VM over what many would see as more “prestigious” programs because it was unique in its focus on clinical quality, one-on-one teaching and its national reputation in regional anesthesia and pain management. It was one of the best decisions I have ever made, but it came with a cost. It was intense. My residency group was small compared to bigger academic programs – only six residents per year, but we were held to extremely high standards and were relentlessly and constantly evaluated. It was impossible to shrink into the background there. On top of that, the senior residents had a huge amount of power over the junior residents in making the weekly call schedule and daily assignments. Some chief-residents were skilled and empathetic in their approach to managing their juniors, others not so much, and hazing was commonplace.

This is an often-uncomfortable repeating pattern in the process of becoming a doctor. A combination of confidence, humility and willingness to being hazed a little bit is part of being a resident. Respect of the hierarchy, while knowing when to push the limits within reason is critical to one’s success. On the other hand, excessive cockiness, a know-it-all attitude or being overly independent - operating above one’s knowledge, experience or skill is severely frowned upon. It’s a stressful balancing act.

I walk back to the ICU to wait for the results of the scan. I know we will be getting this patient sooner or later. If the CT reveals broken bones, or internal bleeding from ruptured organs or a vascular injury in the brain, she will have to go directly to surgery, and we will receive her in the ICU after that. Sooner than I was expecting, however, I get a page from the ICU fellow that she will be coming immediately to us from the CT scanner. Surprisingly, there is no evidence of internal bleeding or fractures, and I breathe a sigh of relief for her. I am the point resident in the case, and I sit waiting at the nursing station outside her room in the ICU for her to arrive. I am also looking for the formal radiology read from her CT scan.

As I made my way to the huddle of morning report, I took note of the faces, names on badges, and demeanor of the assembled crowd. It is easy to spot the medical students. They look lost, wear short white coats, pockets bulging with reference books, plastic formulary guides and various medical tools such as otoscopes, penlights and reflex hammers. An overly expensive top of the line stethoscope is invariably draped around their necks. These talismans and security blankets of medicine are comforting to the newly initiated clinical trainees and help ward off the panic of not knowing what to do.

The internal medicine residents have slightly longer coats, less stuff in their pockets, and give off a subtle air of detachment and intellectual superiority compared to the surgical and anesthesia residents. The latter two groups are often hard to differentiate at first, but once they start “doing”, the differences are obvious. Surgery residents are often aggressive and dominant much to the annoyance of anesthesia residents who by temperament are usually a little more relaxed, especially when it comes to procedures. Maybe it’s because the anesthesia residents have performed ten times the number of vascular access procedures compared to every other resident, and hundreds more intubations. However, the surgery residents can’t help but try to take charge. It’s in their nature.

The ICU fellows run the show with help from the seen-it-all-but-rarely-seen faculty attendings. Attendings are almost always the only ones not wearing surgical scrubs and are often found in their office, or in their research labs and do their best to trust, delegate and ensure that the fellows have things under control. Typically, the attending will round with the team in the morning and in the late evening, equally dispensing wisdom and engaging in the time-honored tradition of “pimping” - the unending litany of complex medical questions designed to humble and keep in line even the most encyclopedic residents and students. Otherwise, they make themselves scarce.

I hear the bed coming down the hall and see the trauma bay gurney with my patient being wheeled feet first into the room. I recognize one of the ER nurses at the head of the bed take over ventilating the patient while the RT comes into the room to set up the ventilator. I don’t know whether or not the young woman was sedated at the scene, or when she arrived at the hospital, or not at all, but there are a few bags of IV fluid running along with a drip of some medication into her IV and she is unconscious. The cables of the transport monitor are shifted to the wall monitor and I look up at the screen and note the red arterial waveform, the ECG spikes revealing a sinus tachycardia, the pulse oximeter waveform correlating with the ECG and an oxygen saturation of 98 percent. The blood pressure is a little high, but otherwise things are looking pretty normal. The team lifts her off the gurney and off the hard backboard and she is transferred to the ICU bed.

To say there was an immediate and unspoken sense of rivalry between all of us members of the ICU team is an understatement. My team included a very aggressive medical student – a gunner, in medical school parlance, who was trying very hard to show off his newly acquired knowledge, and attempt as many procedures as possible despite his lack of experience and manual finesse.

The medicine intern was shy, quiet and seemingly uninterested or maybe even afraid of getting her hands on a patient. She was smart though, and a great source of information about each of our patients. She was also an efficient data collector and note taker and wrote thoroughly researched histories, problem lists and progress notes. We relied heavily on her ability to quickly gather information and on her almost photographic memory of diseases, medications and protocols.

The second-year surgical resident was just plain obnoxious. He was a UW resident planning on a career as a trauma surgeon, and a total stereotype of the aggressive, in-your-face alpha-male. I did my best to avoid him, but we worked too closely for this to be a long-term solution to our mutual enmity. It took a while, but we eventually came to an uneasy truce as the first two weeks wore on and we both came to appreciate our respective skills in managing patients. I helped him out early on with a difficult airway and a few central lines, and I could tell that he grudgingly trusted me. As the month progressed, we each acquired our own patients, and other than rounding we barely had time to interact with each other.

On the second week of the rotation, I began taking care of the boy who had attempted suicide and had blown off his face. He had already been in the ICU being stabilized for a little over a week, but the resident taking care of him had overlapped with me and was finishing his Harborview rotation and transferred back to the main medical center at UW. So, I took over, at first in the intensive care unit, and then in the step-down ward once his acute life-threatening injuries were taken care of.

My job, other than the daily debridement of his massive facial wound, was to gather and report the results of all the daily lab tests to track his condition. “What is his blood count today, Dr. Swisher? What is his acid-base status? Are his electrolytes normalizing?” I learned on an actual patient, rather than abstractly in a book, about a condition known as SIADH, or “Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone” secretion, that often occurs after a concussive blow to the head. Serum levels of the electrolyte sodium go out of whack, and when the levels get too low it can be lethal.

I became a meticulous record keeper and diligently followed every drop of fluid and milli-equivalent of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium that flowed into his veins and later through the feeding tube that snaked down the hole that used to be his nose, into his stomach. I learned a great deal of physiology and medicine from taking care of him and still remember my feeling of pride and competence after replacing an infected central line or working inches away from him with surgical magnifying loupes, carefully debriding and picking away the damaged flesh that used to be his face so that he would eventually be able to have surgical reconstruction and skin grafts. I did this every day for nearly a month. To me, at the time, it was the ultimate doctor patient relationship. It was practically intimate. And now, looking back, I am not so sure… To my regret and shame, I don’t have a single recollection of talking with him about things other than what I was about to do to his body, though I must have. I would like to think I did, and hope I did, but I don’t know. I certainly don’t remember talking to his mother who sat in the corner with a pinched and pained expression on her small and prematurely wrinkled face. It was the face of profound loss.

I never once saw his father, nor any visiting friends. Did he have any? I didn’t know. Why did he try to kill himself? I didn’t ask, and he certainly couldn’t tell me. Even if he could somehow communicate, I didn’t have the emotional experience or maturity to know what to ask, or how to ask it. My colleagues and immediate superiors didn’t help, nor recognize that I was having trouble processing the grief that welled up in me every time I entered that room to take care of him. At a minimum, I recognized that being an emotionally helpless resident on a trauma service confronting the problems of the world is hard, but being an isolated teenage boy is much harder. As the weeks passed, I became inured to working with him, and looking back, must be honest with myself that the experience hardened me, preparing me for far more difficult and challenging situations to come.

Once she is settled into her room in the ICU, and all the monitors, IV lines and medications are sorted out and in place, I take a long look at her before listening to her heart and lungs and performing a quick neurologic exam. Other than the fact that she is unarousable, and on a ventilator, it is as if she’s simply taking a nap. She is beautiful in the way that only a young girl on the very edge of womanhood can be. She has perfect unblemished skin, long blond hair and a small slightly upturned nose. Her eyes are crystalline blue, and her pupils are large and dark, like a doll made of flesh and blood.

I immediately think of the character Aurora, in Sleeping Beauty, but put that thought out of my mind, as it seems disrespectful, and I am certainly no Prince Charming ready to wake her up with true love’s kiss. And I know upon examining her that even if such a thing were possible, it would not be in this young woman. Her pupils are fixed and dilated, and do not constrict even the slightest with a passing of my penlight. Her “C-spine”, or cervical spine had been cleared by the initial X-ray plain films that were taken in the ER and did not show any evidence of fractures or displacement, so I am able to perform a specific reflex exam. Her “doll’s eyes” are, in medical parlance, “absent.” A person with an intact brainstem will still have an oculo-cephalic reflex. She has none. In severe brainstem injury, the eyes remain fixed in their sockets and do not move opposite to the direction that the head is turned. These are both terrible signs. I do one final test. I go to the bottom of the bed and with a tongue blade split longitudinally down the middle, scrape the sole of her left foot. Her big toe points up and the rest splay out, and she does not wince or try to pull away. This is called the Babinski reflex, and while it is positive in newborns, it further confirms the diagnosis of severe brainstem injury.

Back outside her room at the nursing station, I page my fellow to give report and see that the radiologist’s read of the CT scan has arrived. It is worse than even I expected. Her upper brain, the cerebrum, subjected to sudden deceleration in the car crash had kept moving forward, while her spinal column and brainstem held in place by her seatbelt and her airbag had not kept pace, shearing one from the other. Miraculously, she did not suffer any other significant internal trauma and survived long enough to be intubated in the field, ventilated and transported to Harborview. But there is no hope for her recovery. She is in that liminal space between life and death.

A few hours after my girl with the brainstem injury was airlifted to the hospital by helicopter, her parents and family arrived by car. As a parent of three children, I cannot imagine what that drive over Snoqualmie pass and to Harborview must have been like for them. I was paged to meet them in the waiting room just outside the ICU and still remember the visceral feeling of dread and the empty pit in my stomach as I walked down the hall to this room. Other than her parents, I wasn’t sure who would be there with me and if the news of her condition would be delivered before I got there. Surely one of my fellows, or an attending, or a pastor, or a social worker had already spoken to them and would be there to help deliver this crushing information?

But no. It was just me. I was alone with them.

I had just talked with my attending, and he had gone over the films and reports, and examined her as well, repeating the tests I had already done. Neurology and neurosurgery had been by and repeated the physical exam, gone over the scans and had both written notes confirming the worst. The neurosurgeon had suggested that she would promptly need a bedside procedure to place what is called a “bolt”, a device that is placed through a dime-sized hole drilled through her skull to drain spinal fluid and measure the pressure inside her cranium. Over the course of a few hours her brain would start to swell from the injury and from possible intracranial bleeding, and if this pressure was not relieved, her brainstem would herniate through the large hole in the bottom of the skull called the foramen magnum, and that would cause her blood pressure to rise dangerously and then plummet, and her heart to slow and then arrest completely. But despite this intervention, both the neurologist and the neurosurgeon had agreed that her injuries were incompatible with survival, and there was nothing anyone could do. It was just a matter of time. Donor network had already been contacted. All that was left was to talk to her parents.

“Hello, I am Dr. Jeff Swisher, I am the ICU resident taking care of your daughter. I am so sorry this happened. Is there anything I can do for you?”

They stare at me, clearly stunned and anxious. They look me up and down, and I can sense they are trying to figure out who I am.

“I am sure you have a lot of questions, and I can tell you what I know. I am the anesthesia resident on the ICU service. My attending doctor should be coming by soon and he can give you more information as well.”

Suddenly, they seem to emerge from a trance, and they go from silence, to flustered chaos. It causes me to back up a step, and I feel like I am losing my balance.

“Yeah, you can tell us when we can see her! Is she awake? Is she asking for us? Does she know what happened - that her boyfriend didn’t make it? They said we can’t go in and see her right now. Why not? Is she hurting? How long do you think she’s going to have to stay here. They said she can’t talk because there is a tube in her throat! Why is that? Is she hurt bad? When can we go in?”

And on and on. I can’t get a word in, as one after another of the people in the room begin another round of the same, desperate questions.

I remember feeling overwhelmed by the rapid-fire inquiries that first came from her father, and then the same frantic cascade of questions from her mother, and then again by another relative who could have been her aunt. Two other people were with them, and I didn’t know who they were, but it felt like I was being mobbed by all of them. They were obviously frantic for information but didn’t let me answer. One question followed another. As they kept peppering me, I could tell that they were scared but at the same time frustrated and a little put off by me. Perhaps I wasn’t what they expected when they were told the “Doctor” would come talk to them. I have always looked younger than my age, lacked gray hair and was a little unkempt and unshaven from being on call the night before. Most new doctors have imposter syndrome, and in this moment, I felt I had the worst case of it in medical history. I took a deep breath and waited, and finally there was a break in the tumult, and then it just came out. All of it.

“I am so sorry, but the accident was severe. Your daughter has suffered an irreversible injury to her brain, and she will never wake up. She can’t breathe on her own and it is only a matter of time before she dies. There is no chance of recovery. Again, I am so sorry to have to tell you this.”

I heard these words as they came out of my mouth as if I were someone else watching me say them. I told the harsh, unfiltered, unvarnished truth…because I thought it was the right thing to do. Not knowing any better because I had never been in this situation before, I was never taught how to talk to families about a tragedy like this. Looking back on my blunt, hammer-blow delivery of this horrific news, I shouldn’t have been surprised by their reaction. But I was. And I wasn’t prepared for it. They were stunned into silence for several seconds. This was followed by a noise that sounded like an increasingly loud, revving-up air-raid siren – an unnatural keening and wailing and then an explosion of grief. I felt a roaring in my ears, and the rushing of blood inside my head and I nearly passed out. As if I was in a dream state, I distantly heard someone shrieking, “No! No! No!” and I couldn’t be sure if the sound was my memory of that awful day that my mother heard that my father had died. I was suddenly seven years old again, reliving that moment.

And then just as quickly, like a cold splash of water, or a slap across the face, they became angry and called me a liar. I was shocked back to reality, briefly afraid that the father was going to attack me, as he stared into my eyes, inches from my face, heaving great breaths. And then he stepped backwards and went limp into the arms of his wife. I didn’t know what to do and most certainly didn’t know what else to say. So, I retreated. I mumbled something about giving them time, promising I would be back with someone else more equipped to help them. I backed up, turned, and almost bolted from the room.

I was called into my attending’s office a day or so after my encounter with the family and was told that they didn’t want to see me again and requested that I didn’t participate in the care of their daughter anymore. I remember feeling ashamed, then confused, and then angry at them which made me ashamed even more. I was a good doctor, I reasoned. How could I have done anything else but tell them the truth? What should I have done differently? I was never counseled, nor given any sympathy or understanding for my confused, self-critical feelings. I just absorbed them and promised myself that next time I would do better. Next time I would show more empathy and kindness. Next time I wouldn’t fail…

I think a lot about these two patients so many years later, even after a lifetime of experience in medicine and having cared for thousands of patients, most who have made it and a few sadly who have not. As a transplant anesthesiologist, I have witnessed countless tragedies and have worked on donors who have died similar deaths to the young Briar Rose I briefly cared for so many years ago. I have met their grieving families and have learned how to talk to them and how to stay silent and give them the space they need. Mostly I have learned the power of empathy. Unlike sympathy, which is feeling “for” someone, empathy is feeling “with” another person. It is taking on their grief as if it is your own. It is powerful and it is healing, and it is the one true tool that has helped me most to get over my bottomless feelings of regret.

I have been married nearly thirty-five years now, raised three children to adulthood, and have been a good son, brother, husband, father and friend - I know with all my heart that I should forgive my younger self for the sins I have committed – the ones I believe I have committed. But regret has proven to be a heavy burden that is hard to put down. I continue to learn, however, and bit by bit I am beginning to know what it will take to relieve myself of this pressing weight, and that grace and forgiveness is possible. I hope the day will come when I can finally let it go.

March 22, 2025 - Larkspur, California

This was difficult to read in the best way. You didn’t just describe trauma, you brought us inside the quiet spaces where it lives long after the chart is closed. That’s the part medical training rarely prepares anyone for. The procedural checklists are endless, but no one really tells you how to sit with another person’s grief, or your own, when there’s nothing more to fix.

The boy with no face, the girl in the ICU, the parents in shock. I kept thinking about how often young doctors are expected to absorb tragedy without being taught how to process it. It becomes muscle memory to power through, but that comes at a cost. I know that silence. I’ve felt that disconnect.

I don’t think your younger self failed. I think he showed up the best way he knew how at the time. The fact that you still carry these moments, still give them weight, is what makes you the kind of doctor people hope to meet on their worst day.

Empathy isn’t something you’re handed in orientation. It grows in the spaces where you feel like you said the wrong thing, or not enough. Thanks for writing this the way you did. You gave those two kids a name again. You gave their parents a room full of readers who might understand a little more now. And you reminded all of us how much of healing happens when we stop trying to solve and start listening.

Wow. Jeff, it took a lot of courage to write this article with such honesty and vulnerability. Powerful. People aren’t aware the awesome responsibility that comes with being an anesthesiologist. I just came back from my niece’s “Match Day” which, as you know Jeff, tells the student where they will be doing their residency. She chose anesthesiology. I hope her residency program offers some type of skilled training in counseling and empathy when dealing with patients and their families. I’m sorry you weren’t afforded such an opportunity and had the counseling part on the fly. You clearly already had the empathy. I hope you can fully forgive your younger yourself. I’m certain the family has. Thanks for sharing.