The New Frontier

A Son's Memories of his Father's Role as a Mercury and Gemini Program Physician, and a Captain Recalls his Life at Sea

The New Frontier: A Son’s Memories of His Father’s Role as a Mercury and Gemini Program Physician, and a Captain Recalls his Life at Sea

Note to the reader:

This piece is a collaboration between two friends who met on this platform and who are both authors of their own Substacks - Dr. Jeffrey L. Swisher, an anesthesiologist in a large multi-specialty private anesthesia practice in San Francisco, and Stephen Chamberlin, CAPT (Ret), USCG. Both have a lifetime of experience to draw from in their respective fields for their stories and essays, and both have a keen interest in American history and the people who have defined and inspired us.

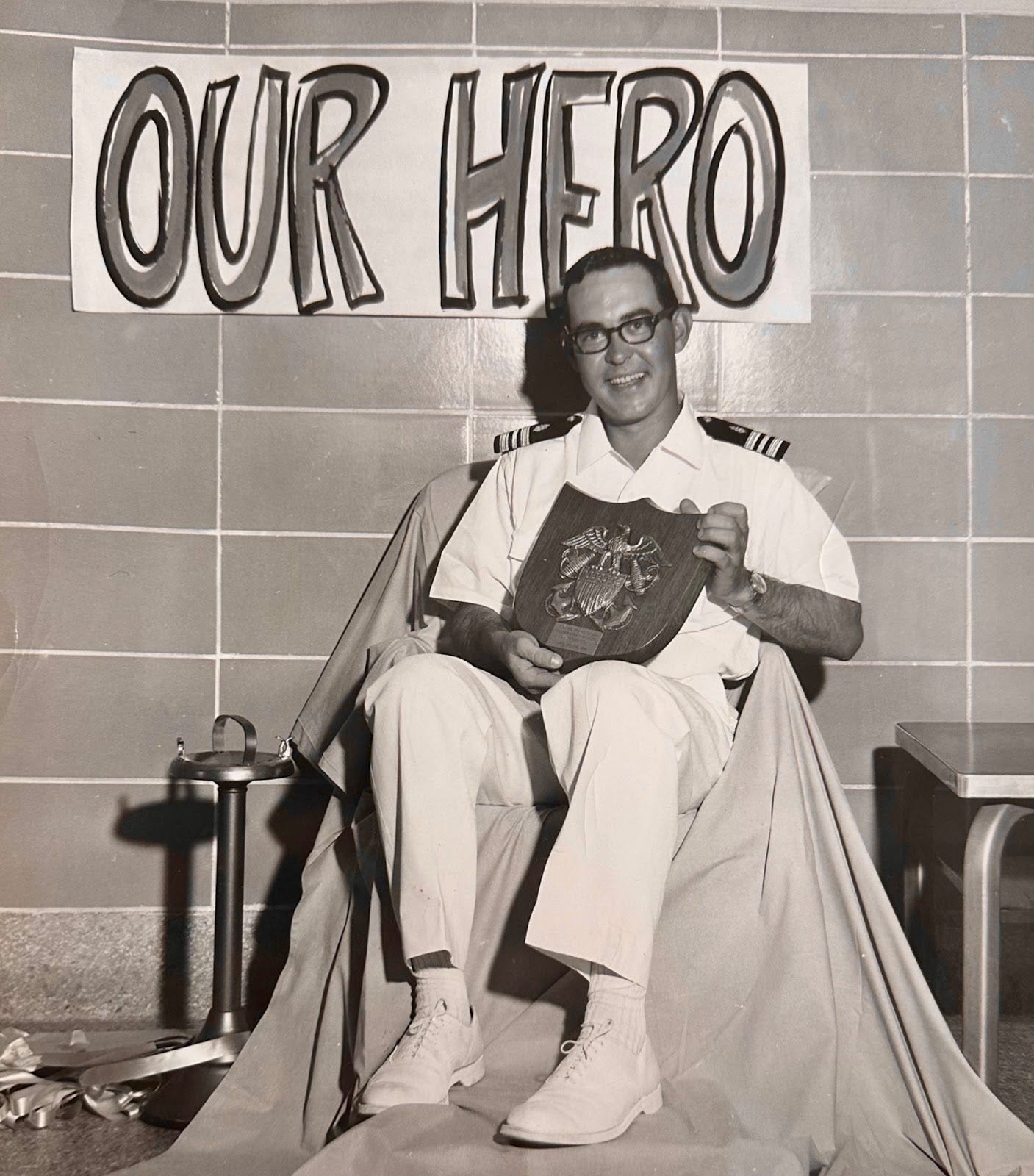

For Dr. Jeffrey Swisher, a letter written to him on May 16, 1963, by his father, LCDR Louis Bush Swisher, Jr, M.D., aboard the USS Epperson on the day of Major Cooper’s return on the last Mercury mission flight, provides a unique insight into that time more than sixty years ago. Lieutenant Commander Swisher was a young Navy officer and one of the doctors charged with caring for Major Cooper prior to his launch and upon his return from space.

For Captain Steve Chamberlin, his recollections of his own sea service on a Coast Guard cutter (ship) in the Western Pacific have given him a wonderful perspective onto the world of the brave men and women who dedicate themselves to the service of our country. He provides colorful and fascinating details about what it was like to be deployed and responsible for the defense and protection of our country and for the lives of those who served with him.

As this piece is a collaborative effort, much of the writing was done by us sharing our thoughts and going back and forth with our edits. Where it is written individually, we will note that in the paragraph header.

Dad

(Jeff’s story)

The words are penned in blue ink on fine translucent onion-skin paper in a neat and fluid, evenly spaced script, carefully written by a young man from a different time.

May 16, 1963

Dear Son,

Your father is now on the North Pacific Ocean about 200 miles north of Midway Island. Today at noon an astronaut landed from outer space about 50 miles south of our ship. Your father is now steaming south toward Hawaii and as soon as he arrives, he will fly home to see you, Kara and your mother…

The letter is folded into an envelope that has been tucked into the yellowed and now slightly moldering pages of “My Baby Book”, a chronicle of my birth and the first year or so of my life. My mother kept this journal until my sister was born and she probably got too busy, or gradually lost interest in the project, or both. There was no baby book for her.

But this weathered time-capsule has traveled with me since I left home for college in 1978. It was one of the few childhood mementos I took away with me, because I knew that if I left it home, it would have disappeared along with almost all my other possessions I left behind. My lost treasures included an autographed baseball of the entire Miracle Mets lineup from the 1969 World Series, a signed copy of the menu from Rocky Marciano’s restaurant and even boxing gloves that once belonged to Cassius Clay before he became Muhammed Ali!

Henry Ventre, my grandfather, was an avid sports enthusiast who occasionally promoted boxing prize-fights and served for a time as the President of the "Friends of Boxing". As a child, I accompanied him to many historic fights as well as many baseball games in the mid to late 1960’s, and can still remember the shouting and the smell of cigar smoke and roasted peanuts, while my grandfather proudly introduced me to sports celebrities and his many, many friends.

Everything that was mine was eventually tossed in the trash when my mother and stepfather sold our home in Princeton and moved across the country to Belvedere, California, exactly 51 miles from my dorm at Stanford – 2884 miles closer to me than when I left home. I still miss my large collection of books and picture atlases, Compton encyclopedias and my dad’s old medical books from his time at Jefferson Medical College. It all went into the trash. I often think about my favorite book – a chronicle of the United States’s space program, from Mercury to Apollo.

But I rescued the Baby Book. Inside its pages I keep mementos and memories of a life that seems long ago and very far away. I never returned home for any great length of time after my freshman year, a week at the most, because I just couldn’t. I finally understood the words of Thomas Wolfe and realized like many young people do that I could never return. Once the Princeton house was gone, there was no “home” to go back to.

Now, more than sixty years later, I have made peace with what I have lost and have forgiven my mother’s carelessness in her futile attempt to erase the past and her grief over the loss of my father, and move on. I think of her as one thinks of a shark, sleek and forever in motion, unable to stay still in one place for too long or risk suffocation.

I open the pale blue padded covers of the book again, and leaf through its pages - my birth announcement, the Western Union telegram from the commander of the Philadelphia Naval Hospital congratulating my parents, the time capsule of greeting cards clearly designed in the late 1950’s - one of an angular mid-century modern cartoon housewife and husband wearing academic mortar boards - “What a clever couple! You discovered that 1 +1 makes three!”

The letter is neatly tucked into the pages of the middle of the book, between my growth chart from birth to age one, and the page delineating the foods that I liked to eat in my mother’s beautiful handwriting– “watermelon with salt, just like his father!” The envelope and single sheet of paper is one of the only tangible possessions I have left from my dad, Lieutenant Commander Louis Bush Swisher, Jr. M.D., who died suddenly and very unfairly in 1968 at the impossibly young age of 34, of a ruptured cerebral berry aneurysm. He died just shy of five years after he wrote this letter. I was seven years old, and this letter is the only direct communication from him to me that remains.

But on that sunny day in May, somewhere on the vast and blue North Pacific Ocean, aboard the Navy destroyer, the U.S.S. Epperson, he took time to write me, his firstborn son, to memorialize the momentous journey of Major L. Gordon Cooper, Jr. the last of the “Magnificent Seven” Mercury astronauts to be launched into orbit solo, ushering in a new decade, and the beginning of the age of space exploration.

Please tell your mother to save this letter and especially this envelope for you until you are bigger and can read it for yourself. The envelope is just paper now but in about 20 years will become a collector’s item as there are only 50 now in existence and by then there will be very few. This will be in the history books by the time you go to school, and you can show it to your friends then.

This final successful Mercury mission, the capstone of a total of six, was the bookend of one era, and the beginning of a new, far more tumultuous one. It was, in many ways, the end of American optimism and innocence, and the threshold to a far more complex, cynical and dangerous world.

By the end of 1963, John F. Kennedy, the young, dynamic American President would be assassinated in Dallas, a war in Viet Nam would needlessly escalate, ultimately costing over fifty-thousand American, and well over three million Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian lives, a Cold War, between America and the Soviet Union and resultant nuclear weapons proliferation would dangerously expand, threatening humanities continued existence. On a much more personal but no less important level, with the untimely death of my father, my life, and the lives of my mother, sister and younger brother, born in 1964, were forever changed.

As I fold the letter and put it back into the envelope and carefully tuck it once again into the pages of the baby book, I close my eyes, smile and remember him. My thoughts take me back to that day in 1963 and wonder what it was like for my father on that ship, staring up into the endless sky, scanning the horizon for a glimpse of a giant white parachute holding aloft a small gray capsule containing the lone Major Cooper, and the dreams and prayers of all humanity. For a brief and miraculous moment, Gordon Cooper was the “fastest man” in the history of mankind. His accomplishment and those of the countless number of scientists, engineers and workers who made the journey of Faith 7 and its speed of 17,546 miles per hour, 22 orbits of the earth and 34 hours and 20 minutes in space possible will always be remembered and is indeed in the history books. My dad was one of the people who helped on this quest, and for that I will always be proud of him.

Your father was one of 25 doctors who waited around the world to take care of Major Cooper when he landed.

I have so many questions about that day and about that letter that I would love to ask. A lifetime of questions that I would give anything and everything for him to answer.

Why did you join the Navy, and how did you get assigned to be part of the Mercury program?

What was it like to be on a small ship in the middle of the giant Pacific Ocean?

Why did you write the letter the way you did, in the third person?

Did you know somehow that you wouldn’t be around to read the letter to me yourself?

Did you miss me?

Do you know how much I still miss you?

I hang on to the last three words of the letter, and repeat them to myself once again, like I have for the last forty years or so since I first found it in a manila envelope in a dusty drawer of an old filing cabinet that was destined for the dump on one of the many moves that happened after my father died, and I could read the letter for the first time by myself.

The last four words are like small feathers, or balloons rising to the sky, swept away by the wind, or like the sparks of a campfire, burning brightly and then in an instant… gone.

All my love,

Dad

Into the Wild Blue…

(Jeff)

On April 14, 2025, on a private ranch in a remote area of West Texas on a perfect, sunny blue-bonnet day, six women fashionably arrayed in cerulean blue, form fitting jumpsuits emblazoned with a specially designed Blue Origin NS-3 mission patch embroidered with small symbols - a firework, a microphone, a target star, a film reel, a scale of justice and “Flynn the Fly” representing each of the crew, climbed into the comfortably padded capsule of Jeff Bezos’ commercial sub-orbital rocket aptly named the “New Shepard” in honor of Alan Shepard, the first American in space, and buckled themselves in for launch.

The all-female crew included two celebrities, Katy Perry, a well-loved pop-singer of such hits as “Firework” and “Eye of the Tiger”, and Gayle King, TV entertainment journalist and best friend of Oprah Winfrey. It was rounded out with Lauren Sanchez, girlfriend of Jeff Bezos, the billionaire owner of Blue Origin, film producer Kerianne Flynn, rocket scientist Aisha Bowe, and the quite impressive Amanda Nguyen, Harvard graduate and bioastronautics research scientist who was one of Time Magazine’s Women of the Year in 2022 for her activist work on sexual assault.

Their 11 minute completely automated flight brought them to the edge of space, just beyond the Kármán Line, 62 miles above sea level where the atmosphere is too thin for aeronautic craft to fly. It is where the sky turns from blue to black, but not quite high enough to achieve earth orbit. This requires an altitude half again as high and a much greater velocity.

There was much hype and hyperbole surrounding this multi-million-dollar junket into space. Anyone who can put down a $150,000 deposit and pay the undisclosed balance can reserve a seat - one of the original crewed flight’s tickets sold for $28 million at auction! Words like “historic” and “feminist” were used to describe this charitably described luxe space mission.

Gayle King, in response to the many critics who derided her comparison to the original flight of Alan Shepard in 1961, said “Have you been? Please don’t call it a ride….We duplicated the same trajectory that Alan Shepard did back in the day, pretty much. No one called that a ‘ride’. It was a flight; it was called a journey. There was nothing frivolous about what we did.”

The words “pretty much” do a lot of heavy lifting here. To be fair, any ride, journey, or mission that begins in a capsule, no matter how cushioned and comfy, strapped in above a ballistic rocket filled with highly explosive liquified natural gas and liquid oxygen takes a considerable amount of intestinal fortitude and faith in technology.

However, anyone who seriously believes that the Blue Origin New Shepard flight is anywhere comparable and equivalent to the original Alan Shepard Mercury flight, or any of the subsequent Mercury, Gemini and Apollo flights does not understand or appreciate the limits of 1960’s technology or the immense skills and experience of the test pilots who comprised the original astronauts.

The End of the Beginning

(Jeff and Steve)

Major L. Gordon Cooper was the last of the Mercury Seven astronauts who pioneered the solo journey into space in the early 1960’s. Cooper and his colleagues flew six missions of increasing risk and complexity in the short span of two years. From Commander Alan Shepard’s first flight atop a Redstone rocket on May 5 of 1961, to Major Cooper’s flight atop the more powerful Atlas-9 rocket on May 15th of 1963, they each traveled alone from the safe embrace of the earth to the very edge of space. Following the initial flight of the Soviet Union’s Yuri Gagarin atop Vostok 1 in April of 1961, they were the first Americans to venture in claustrophobic capsules perched atop powerful intercontinental ballistic missiles initially designed to carry nuclear warheads, not men.

The technology of the time seems practically primitive compared to what we have today. Our cell phones and desktop computers have more power than anything available then. In 1962 the IBM 7094 computer, one of the more advanced computers in existence, was capable of an astonishing 0.35 MIPS (millions of instructions per second). It was the size of a large refrigerator and weighed over two-thousand pounds!

A modern iPhone 16 pro in contrast does not even measure processing speed in MIPS. It has a much more complex architecture and parallel processing capacity and a miniaturized GPU that can achieve up to 2.58 teraflops (trillion of floating- point calculations per second). It weighs seven ounces.

There were no onboard computers on these rockets of any size. All navigation calculations had to be performed on the ground and radioed to the astronauts analog style. They used pencils and slide rules. Their skills as test-pilots, navigators and mathematicians on the fly were repeatedly put to the test in potentially life-threatening situations whenever something invariably went wrong. Speed of thought and action, as well as accuracy of analysis and appropriate response were critical. As a testament to their intelligence, composure under pressure and piloting ability, six of them (Deke Slayton was grounded due to an episode of atrial fibrillation, but finally flew into space in 1975 on the first international joint Apollo-Soyuz project) successfully completed their missions, safely returning to earth, despite the risks and the significant odds of failure.

Happy Days Are Here Again

(Steve)

In times of crisis and chaos, the human tendency to romanticize the past becomes particularly acute. We are currently in a period of crisis and chaos – where uncertainty and doubt about the future is particularly worrisome.

While romanticizing the past does tend to wash out the real challenges of those times, it can also give us hope for the future.

The post-war era in the US from the late 1940s through the early 1960s was packed with challenges: the Korean Conflict, the beginning of the Cold War, and growing unrest about civil rights to name some of the more significant issues.

Concurrently and on a more positive note, the Cold War indirectly kicked off the “Space Race”. Allied success during the war and the leadership role the U.S. assumed following the war, fueled belief in American exceptionalism. American citizens believed we as a nation, working collectively and with purpose could achieve anything. This was made manifest in the space race.

The literal “Sputnik Moment”, when the U.S. realized the Soviet Union had “beat us” and put a satellite into space, sparked a period of incredible technological achievement – directed by a relatively unified, well-functioning U.S. federal government.

From NASA’s founding in 1958 and the launch of Explorer (the U.S.’s first satellite and a direct response to Sputnik), to the 1959 start of the Mercury program (putting an American into space), to President John Kennedy’s moon speech in 1961, the Gemini program, and ultimately the Apollo program which put humans on the moon in 1969, the U.S. defined the power of what “good” government could do.

To the Moon, Alice!

(Jeff)

The Mercury program was the U.S.’s first step on its journey to the moon. Project Mercury was conceived and designed to accomplish the goal of first putting a man into space, and then into earth orbit. The Mercury flights paved the way for the two man Gemini missions, then the three man Apollo crews and the first moon landing in 1969, less than a decade after the launch of the first man into space.

Eventually the mammoth cost of the Apollo program, a decreased public interest, an increasingly costly war in Viet-Nam and a worsening economy led to a scale-back in government funding for NASA.

Despite these setbacks, the space program continued. Skylab was launched in 1973. Three separate astronaut crews inhabited the orbiting laboratory setting space endurance records, until its last mission ended on February 8, 1974. Eventually Skylab’s orbit disintegrated and it had a fiery re-entry in July of 1979 leaving a debris field that stretched out over 2,500 miles with sonic booms and large pieces of the station falling in largely unoccupied Western Australia.

Then there were the many space shuttle missions. STS-1 launched with a two member crew on April 12, 1981, proving that an orbiting spacecraft could be launched, return to earth aeronautically, and be reused again. There would be five such shuttles - Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour. A total of 135 missions were flown for a total of 1,322 days in space.

Few Americans alive at the time can forget the twin tragedies of STS-51 Challenger in 1986, and STS-107 Columbia in 2003. In the former, an O-ring, deformed from the unusually cold weather on launch day, failed, causing an explosion of the solid-rocket booster leading to a much greater explosion of the larger liquid fuel tank and disintegration of the craft one minute and 13 seconds into the flight. Seven astronauts perished in the accident, including the first civilian teacher in space, Christa McCauliffe, as an entire nation watched in frozen horror.

The second tragedy occurred on February 1st of 2003 resulting from damage to the thermal tiles on the left wing edge due to a piece of solid insulating foam debris that broke off from the solid boosters during launch. Despite prior occurrences of this on preceding space shuttle flights, NASA engineers knew this was serious, but could do little about it, save from preventing the shuttle from landing, which was impossible at the time. Upon reentry of STS-107 the loss of integrity of the heat shielding tiles and the entry of superheated gases into the internal structure of the wing led to the catastrophic disintegration of the craft above Texas and Louisiana. All seven astronauts perished.

The shuttle program was suspended for two years and emergency contingency plans were created to use the ISS (International Space Station) launched in 1998 and continuously occupied since 2000 to act as a lifeboat should problems be discovered on future shuttle missions. Despite this, NASA retired the space shuttle program after 30 years in 2011 with STS-135.

The commercial Blue Origin and SpaceEx flights owe their existence to all that came before. The original Mercury flights, while marvels of engineering, human skill and bravery were technologically primitive, and far riskier than modern space flight.

Each astronaut was strapped into an uncomfortable and cramped six by eleven foot capsule, and literally bolted inside. They wore a thin pressure suit that barely insulated them from the cold and were far less sophisticated than modern spacesuits. They were trained and conditioned to sustain prolonged periods of both high G-forces as well as weightlessness. While each mission was largely flown ballistically and then on autopilot, each astronaut had to have the skill to manually fly the capsules in both space and upon re-entry in case automation failed.

And automation did fail.

Major Cooper’s craft, Faith 7 performed flawlessly until his 19th orbit around the earth when a malfunctioning sensor made it seem like his capsule was starting re-entry. On his 21st orbit, the carbon dioxide level began to rise in the cabin and in his spacesuit. Cooper reported to mission control center in in that now stereotypical casual test-pilot drawl, “Things are beginning to stack up a little.”

He then had to do a series of quick calculations aided by the engineers on the ground to manually fire positioning rockets to re-adjust his flight attitude and safely re-enter the atmosphere in order to finalize the capsule’s trajectory to splashdown in the specified target area in the North Pacific Ocean, thus ending the final Mercury mission.

Call Me Ishmael

(Steve)

As a career US Coast Guard officer who did a sea tour on a Pacific based Coast Guard Aids to Navigation “cutter” (USCGC Basswood, WLB 388) in the early 1990s, my experience was somewhat relatable to that of the crew on the USS Epperson (DD 719) in May of 1963, when the Gearing-class destroyer participated in the mission to recover astronaut Gordon Cooper after his successful, and the final, Mercury mission.

There were some major differences of course. Epperson was a 2,400 ton (tonnage for ships refers to water displacement), 390 ft, 336 crew Navy destroyer.

Basswood was a 1000 ton, 180ft, 60-person crew Aids to Navigation service vessel (also known as a buoy tender).

However, Basswood and Epperson were commissioned in 1944 and 1945 respectively. Moreover, US sea service shipboard routines and technology during the period of the 1940s through my time (1990s) were relatively similar despite their very different missions. Moreover, Cooper was recovered in the Pacific just south of Midway Island. I spent two years a bit to the west in Micronesia.

Life onboard Epperson was, perhaps, a bit more accommodating than on the Basswood (in 1963 it was newer than the Basswood I served on in 1992 and far larger), but the daily routines mirrored each other. The sea services are bound by tradition and routine – many components of the routine dating back centuries.

While underway, officers and enlisted operated on a daily watch schedule of 4-hour watches. The 4-8s two times daily, 8-12 two times a day and the midwatch (12-4) two times a day. In a small crew (like the Basswood) you’d be pulling 8 hours of watch a day indefinity. The crew was also expected to work an 8-4 workday. So, if you had the 4-8 watch, life got rough. The midwatchstanders were theoretically allowed to sleep in until 10AM, but in my experience, as Basswood’s Operations Officer, I rarely got to do that.

The living spaces on both ships were likely set up in a similar fashion: the rear of the ship was “Officer’s Country” with staterooms and a wardroom (dining area) for commissioned officers, a centrally located living space for Chief Petty Officers (senior noncommissioned officers) and forward in the ship (focsle) the enlisted crew slept in open bays.

While commissioned officers certainly had more privacy, at least in the case of the Basswood (where I shared a “stateroom” with another junior officer), it was crowded and dated. I had the upper bunk in a space where only one of us could get dressed or work at a time. I could not sit up without my face hitting an asbestos coated pipe. It was tight.

In the Pacific, for LONG periods we encountered no other vessel traffic. I traveled with Basswood from San Francisco to Hawaii and then onto Guam. On several occasions we were at sea for more than 5 days without encountering a single vessel.

The Pacific has a different feel than the Atlantic. I grew up on the east coast of the United States. The north Atlantic was always dark, moody and mysterious to me. The vast expanse of the Pacific, while diverse - off the northwest coast of the U.S. you experienced the dark and stormy “Atlantic-like” environment - but as you proceed south and west, one word hit me: (lower case) pacific. While I did experience terrifying weather, vicious squalls and several typhoons, much of my transit time was in deep blue, perfectly calm weather. Hot and humid. The occasional flying fish and every now and again, whales breaching in the distance.

The second word is vast – due largely to the fact that I traveled from the west coast to Guam in a tiny ship that at best made 12 nautical miles an hour (12 knots). A nautical mile is slightly longer than a statute mile – 12kts is very slow.

As has been the case for centuries, life at sea on a military vessel tends to become monotonous: standing watch, doing work, standing watch again…the day revolves around watches, work, meals in the galley (lots of bad, burnt sea service coffee) and sleep.

Life on the Basswood was this way and life on the Epperson was this way.

Where the Hell are We?

(Steve)

In fact, even navigation in the 1960s and 1990s was fairly primitive. Epperson and Basswood relied on dead reckoning just as sailors have for centuries. We used paper charts, a magnetic compass, ancient tools, pencils, knowledge of drift and wind conditions and based on the latter factors along with speed and direction we made educated guesses as to where we were and what course to steer to get to our destination.

We did have some navigational advantages over 19th century sailors: Long Range electronic navigation (LORAN) which was based on radio signals sent by fixed land-based stations, primitive satellite systems in the 1980s, doppler sonar and, believe it or not, celestial navigation, with the same tools used centuries ago.

GPS was introduced in the 1990s, around my time, but the best we did with Basswood was to purchase a small GPS unit at a local marine supply store – but we were amazed by its accuracy.

Needless to say, it was all the more remarkable that Epperson, in a naval group led by the small aircraft carrier USS Kearsarge, was able to pinpoint the exact splashdown location of Cooper and his “Faith 7” capsule.

It All Went Sideways

(Jeff and Steve)

The successful launch and recovery of Major Gordon Cooper and his Faith 7 Mercury capsule was the capstone and final mission of the Mercury program. It was in many ways the end of one era and the beginning of another and provided a solid foundation for the subsequent Gemini and Apollo programs.

Cooper participated in the Gemini program as both a backup command pilot and a command pilot for Gemini 5 where he spent 8 days in orbit. He wasn’t chosen to participate in the Apollo program.

Cooper retired from the US Air Force and NASA in 1970 and spent many productive years as an aerospace industry consultant. He died in his California home in 2004 at the age of 77. Senator John Glenn, the second Mercury astronaut to be launched into space, and the first man to orbit the earth was the last of the Mercury Seven to “slip the surly bonds of Earth.” He died in December of 2016 at the age of 95.

The Epperson saw action in the Vietnam War and deployed throughout the Pacific until her decommissioning in 1971. Epperson was transferred to Thailand, and commissioned as an active vessel in the Thai navy.

In the late 1980s or early 1990s the former Epperson was decommissioned from the Thai navy and scrapped.

While the initial Apollo missions did achieve President Kennedy’s goal of putting humans on the moon and bringing them home safely, the program was enormously expensive. Vietnam, and domestic programs encroached as the public lost interest in the Apollo program.

NASA shifted to other, perhaps less ambitious programs such as Skylab, the Space Shuttle and the International Space station. Recently more ambitious projects are being planned – both publicly and privately funded. Interest in human missions to the moon may be realized in NASA’s Artemis program. Communications and other types of satellites are being launched on a weekly basis. But the focus has shifted. Once we celebrated the collective actions of “us” as a nation along with the triumphs and success of good government as a shepherd of the space program. Now we watch mostly disinterestedly as individual billionaires commercialize space travel, and market it as either a luxury experience, or a bizarre project to launch electric cars into space and feed the fever dream of the richest man in the world to colonize Mars.

While it may be the nostalgia of two aging baby-boomers looking back wistfully at our youth, we grew up in a period of high trust, optimism and faith in many of the accomplishments of the American government of the 1950s and early 1960s. While the U.S. was far from perfect in so many ways, we set out in this essay to highlight what WAS accomplished during this time of great technological advancement and change. Thus it was our decision to write about the magnificent events that occurred at a time when they could still capture the world’s attention, and hold it there for a series of unforgettable moments - the first American in space… Godspeed John Glenn… One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind… Houston we have a problem… the space shuttle has exploded…

We hope this provided, if nothing else, a break from the constant deluge of negative news today and the abject cynicism over what seems to be the decline of our government and the loss of civility and co-operation. At best, we hope to recall and instill a bit of optimism for what we have accomplished and are indeed most certainly still capable of achieving.

Post-Script: Mom

(Jeff)

I walk down the long hallway of Inspir, once a fancy hotel near Dupont Circle in Washington, DC that has now been repurposed and remodeled as an upscale retirement facility for financially well off residents who can afford the steep monthly fees.

I am here to visit my mom who insists she is here against her will. She would rather be in her apartment on the upper East side of New York, where she has lived for the last decade or so of her long life. She is nearly 91 years old and despite her denials about both her age and her abilities, cannot live safely by herself anymore.

My sister Kara, brought her to Washington where she could be close by, and is doing the lion’s share of the work to make sure Mom is well taken care of. She visits her regularly, takes her to her medical and dental appointments, ensures that she regularly socializes and personifies everything that a good daughter should be. My brother in Pennsylvania takes care of all of my mother’s finances, and hires the extra help that she needs. But I am in California, an entire continent away, and am not carrying my share of the work. It makes me feel a bit guilty, but I do talk to her every day - often several times a day.

Over the blaring sound of her television perpetually tuned to Fox news, I try to be patient and listen to her constant complaints about how much she hates feeling trapped there. She is an angry, frail bird in a gilded cage. But her feisty spirit is very much intact and is most certainly keeping her alive. While she may repeat a story, forgetting she has told it five minutes before, or perseverate upon some imaginary slight she feels has been inflicted upon her, my mother’s memory is still sharp and reaches long into the past.

I ask her about the letter that was written to me from my father so many years ago…

“Mom, do you remember when Dad went on a mission to take care of the last astronaut of the Mercury program”

“Who?”

“Major Gordon Cooper. Do you remember him?”

“Oh yes, he was handsome. They had a ticker tape parade for him in New York. There were lots of people. I think LBJ was there. He was still Vice-President then.”

Of course I immediately google this while I am talking to her on the phone, and damn if she isn’t correct. The parade was held on May 22, 1963 in downtown Manhattan and more than four million cheering people crowded the streets from Broadway to Union Square, including Lyndon Johnson and former President Herbert Hoover.

“Do you remember a letter that he wrote me from the ship he was on, the USS Epperson?”

She pauses a bit and I think she maybe has lost her train of thought, or was distracted by something on Fox and Friends.

“He was a good man...”

“Who? Gordon Cooper? LBJ? Who was a good man?”

But I quickly realize she is talking about my dad - because he was indeed a good man, and he left her and me, Kara and my younger brother, David far too soon. I can hear the catch in her voice and then a sigh. I think for a second she might be crying. But as soon as that crosses my mind she says,

“No, I don’t remember a letter. Did he send one?”

I am holding the envelope in my hand and consider taking the pages of the letter out and reading it for her, but I choose not to. The letter was meant for me and I decide for now that I want to keep it that way.

I think about the path that letter took sixty-two years ago - from his hand, to the ship’s mail office, then back to shore in San Diego, to a US postal plane and then to the mailman in Haddonfield, New Jersey and finally after many years spent forgotten in a dusty filing cabinet, to me.

I am curious about what he said in the letter about the envelope. How there were only fifty in existence and about his prediction that in the future there would be few left - that it would be valuable. So again, I go to google and search the vast internet for the terms “day of recovery envelope, Gordon Cooper, Mercury, USS Epperson.”

Immediately I find a site for postage collectors called “Morris W Beck Naval Ship and Space Flight Covers.” There is a link to E-Bay with a picture and the price of a similar envelope from one of the other Navy destroyers on the Faith-7 recovery ship task force. Staring back at me from the screen of my cell phone is a picture of the envelope with the familiar cartoon of Major L. Gordon Cooper, Jr.’s crew cut framed head above a drawing of his capsule and the words “Orbits the Earth” superimposed on a red inked Mercator projection map of the seven continents. The price? - Six dollars and eighty-five cents.

I laugh, shake my head and close the page. The site is wrong, and my father was right. My envelope is better than just rare and valuable. It is more precious to me than all the money in the world.

June 5, 2025 - Larkspur, California