The last time I saw John Wallace, my best friend from high school, was at the end of the summer of 1981 in the Panhandle, the little eight block oasis of green grass between Fell and Oak Streets to the north and south, and Baker and Stanyan Streets from east to west, at the entrance to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. I had come up from Stanford for the day to meet with him, and to catch up. Two years had passed since I had last seen him, on a bluff overlooking the Yale campus in New Haven, at the beginning of my cross-country road-trip to return to school in California. After spending the summer living and working in San Francisco, it was now John who was leaving California to return to school in Connecticut.

I had received a letter from him earlier in July saying he wanted to meet whenever I had a chance. John had recently finished his junior year at Yale and come to San Francisco to work as a summer intern at Mother Jones magazine. But he also came for a larger and more important reason – to discover himself, and to finally and fully embrace the person he had always been inside.

I was living in Palo Alto at the time, ready to start my senior year. My summer had been spent idyllically at Fallen Leaf Lake near Tahoe working as a sailing instructor at the Stanford Sierra Camp, an alumni retreat staffed by impossibly young, handsome and energetic Stanford students. If there was such a thing as paradise for a twenty-year-old, this was it. After camp was over and before school started, my friends and I rented a small four-bedroom house on Hamilton Avenue in Palo Alto about a mile from the campus. So, one morning in early September, I phoned John and told him I would be coming up to meet him.

Even though I often thought of him, John and I had drifted apart as many childhood friends do once they go to college. That was especially true for us, as I chose to leave Princeton, the small colonial, historic college town where I had grown up, for the golden state of California. As it turns out, I traded one sheltered, privileged fishbowl for another, as the major differences between Palo Alto and Princeton were the weather and the architecture. I went from ivy covered red brick and slate roofs, to ivy covered sandstone and adobe clay roofs. Otherwise, both were bookends at either end of the country, similar in their wealthy suburbs, easy proximity to a major city, and their “town and gown” environment.

Many of my high school classmates chose to attend Harvard, or Dartmouth, Middlebury or Princeton, Columbia or Yale - John among them. At the time, I thought of myself as a pioneer and an iconoclast in choosing to go to Stanford for college. In retrospect this was somewhat naive, as Stanford had long been an established world-class academic institution rivaling any of the ivies. But few people from my small school had gone there and I felt I was leaving my friends, and everything that was familiar to me for the end of the earth. So, I was happily surprised that summer to hear from John and have a chance to catch up, despite being a little worried by the letter he sent me.

“Jeff, I NEED to see you! I want to tell you something…in person.”

I wasn’t overly concerned, however, because John was always one to speak emphatically, and was often more than a little dramatic. The tone of this letter was somehow different though, and more urgent than the few times I had heard from him over the past three years.

Looking back, I am embarrassed by how many weeks it took me to respond, and of my ignorance, because it was obvious even then what he wanted to tell me. Maybe I didn’t want to understand, or was too immature and self-centered, caught up in my own life to answer him back immediately. So, it wasn’t until the very end of his stay here that I agreed to meet him on a typical hot, then windy, then foggy, then freezing late summer San Francisco day.

I look back on our last time together, our short walk in the park and our awkward, uncomfortable conversation, and I feel so much regret, because it did not go well. I regret my immaturity and how I behaved, and what I said... and what I didn’t say. Far too quickly our time together was over, and we parted. I waved him a quick, hurried goodbye, wanting to get away and intentionally ignoring the obvious hurt in his eyes and the way his arms hung down to his sides, not waving back. I turned and walked away... and never saw him again.

In February of 1990, a little more than eight years later, when I was a medicine intern working ridiculously long hours at a hospital in Seattle, John died of complications of AIDS in New York City surrounded by his loving friends and family. To my everlasting shame, I will always feel that I failed him as a person and a friend on that last day we had together in San Francisco.

Even though I kept up with other friends in the years after who told me about his life and writing career and his finding the person he loved, I never saw him over any of that time. And then I heard that he was sick and about his long illness and decline from the many opportunistic infections, and co-morbidities of AIDS. I never visited him. I never even called him. Most painfully, I never got to tell him how much he meant to me, until it was too late. And I lived...and will continue to live with that regret.

John and I met in eighth grade at Princeton Day School, a small private prep school located in the very quaint town of Princeton, New Jersey. It is typical of the many rarefied private schools that are scattered across the Northeast like so many red and gold autumn leaves that fall beneath the spreading maple, elm and chestnut trees that grace their vast green lawns.

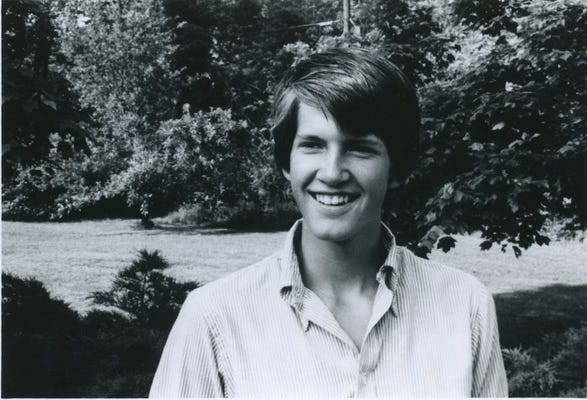

John was one of the most talented and popular boys in our school. In addition to being smart, witty and endlessly amusing, he was a star actor in many of our drama productions. He was a perfect Lord Evelyn Oakley in “Anything Goes” and was even better as Jack Worthing in “The Importance of Being Earnest”. Tall, thin, casually and effortlessly good-looking in that Nantucket, preppy way with sandy blond hair, and a big crooked wry smile, he was the perfect Abercrombie and Fitch male model before such a thing existed.

He was also the perfect date for many of the girls in our class who belonged to “societies” that organized annual dances such as the International Debutante Ball held at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Old time bands such as Lester Lanin played at these events while daughters in formal white dresses were “presented” to society. Whit Stillman’s 1990 movie “Metropolitan” perfectly captures this privileged yet anachronistic coming of age tradition.

The young women are accompanied to these dances by their escorts, two young men, dressed in formal white tie and tail. But there was hierarchy even in that. John was often chosen as the primary escort for the few debutantes in our class, and to those dances I was invited to, was usually the “stag” - the extra young man. It was more of a testament to John’s outsized personality as well as his Jay Gatsby good looks that he was the favorite.

We graduated from PDS in June of 1978. As a graduation present and a rite of passage typical for so many young people the summer between high school and college, John and I planned a six-week whirlwind trip to Europe. Our agenda was ambitious but manageable in the “Europe on Five Dollars a Day” kind of way. We decided to meet each other in Milan as John would be going two weeks before me on a tour of Italy with his family.

It’s hard to imagine now in the era of instant communication, global cellphones, email and text, but our final plans were made by mail in the form of a frantically scribbled post-card sent to me from Rome with a picture of the Coliseum on the front and explicit directions on the back detailing in his small and perfect script where and when we should join each other.

“Jeff, this is very important…I will be waiting for you at the hotel lobby in Milan all day on the third of July! So come as soon as possible – because no matter what time you get to the lobby, I’ll be scared shitless that we won’t connect. So dammit, Jeff, be there!!! If you don’t make it, I will die!!!”

At seventeen years of age, feeling free and independent at last, I flew out of JFK carrying a battered blue backpack, a sleeping bag, a dog-eared copy of Let’s Go Europe, a Eurail pass, and a tent named “Allison” named after both of our high school girlfriends. We found that joke endlessly amusing and repeated it countless times.

As luck would have it, Alitalia lost my backpack on the flight over and for a terrifying day I had my passport, a little bit of cash, and nothing else. I had foolishly packed my traveler’s cheques in my backpack, as well as my return airline ticket and Eurail pass. I was convinced that the trip would be over before it even started. To make matters worse, a pigeon crapped on my only shirt on the way to the hotel, undoubtedly a bad omen. Thankfully, we did manage to meet. John did not die. My backpack was located and returned to me at the hotel, and the next day we set off on our grand adventure!

Over the next several weeks, we made our way across the continent in the second-class compartment of trains crowded with rowdy fellow teenagers from every part of Europe and America. We traveled from Milan to Lac Leman in Switzerland, to empty railway stations at midnight in the middle of Austria, to Munich and the Hofbrau Haus beer garden. We spent rainy days huddled in our tent in muddy campgrounds on the edge of many towns. We learned useful phrases such as, “Wo ist der Bahnhof?”, or “Ou est l’auberge de jeunesse?”, or most importantly, “Un bicchiere di vino rosso per favore!” We feasted on cheese and bread, and cheap red wine. We cooked bowls and bowls of Knorr noodle soup on our camp stove and bought spit-roast chicken and French fries in greasy newspaper cones. We drank far too much beer at summer festivals and once sufficiently inebriated, snuck the heavy glass beer steins out under our shirts, terrified of being caught by the thick, burly guards at the door, and then laughed into the night once we made it back to our campground.

We listened to outdoor symphony music in Viennese parks and took a long and winding boat tour in Germany down the Wörnitz River, visiting the medieval walled town of Dinkelsbűhl, and Mad King Ludwig’s castle in Bavaria. We made our way into France on a train with two beautiful teenage girls from Amsterdam who taught us a drinking song called “Homo in a Kimono”, and how to pronounce the word “lekker”, which means “yummy”, but in that irresistible, slightly naughty sounding guttural Dutch way. I was smitten with these girls and wanted to keep traveling with them, but John did not, and we argued about it.

As we made our way to Provence it was clear there was something more than just the annoyance of being constantly together that came between us. I remember feeling that he wanted something more from me, and I couldn’t understand what that thing was.

The tension boiled over a few days later, and we fought bitterly over who should pay for a melted plastic cowling on a moped that we had rented somewhere in Toulons. The part had gotten too close to the exhaust because it wasn’t meant to be a two-person moped and one of us had used the cover as a footrest. For the first time on the trip, we briefly parted ways over this argument, and then tearfully re-united a day later near St. Tropez, apologizing to each other for letting such a small thing get between us.

We then stumbled upon a classic French bistro with an outdoor patio full of small tables with blue and red umbrellas and a view of the sea and had the best reunion, feasting on bouillabaisse in bright white bowls topped with little floating toasts smeared with saffron mayonnaise. The madame owner of the bistro kindly agreed to serve us despite our look of shock and dismay when we read the menu and nearly passed out at the prices. She led us to a small table towards the back of the patio and with a conspiratorial wink provided this delicious meal at a fraction of the pris-fixe price on the bill-of-fare.

And then, like waking up from an amazing dream, our trip was over, and we headed home. John started Yale early in September and I moved to California a few weeks later to begin my college life.

Over the course of freshman year, I received several letters from John, each one a little less newsy, but more cryptic than the last. In one of the first letters, he described his roommates and the petty squabbles they had. He lived in a quad with three other guys, and had a fight over paying for a toaster oven that one of his roommates bought without asking. He talked about his busy life, his classes his weekend reunion with friends from high school when he visited Dartmouth, rowing freshman crew, playing Schroeder in a college production of “You’re a Good Man Charlie Brown”, and trying out and making a spot on a Yale singing group called the Spizzwinks. He wrote about Yale traditions and the Blue and Gold and Green Cups of liquor at Mory’s, an old New Haven bar. It was all very East Coast-y and different than the experience I was having at Stanford, and it sounded exhausting.

Life for me in California was a little more laid-back. I was learning about Vuarnet sunglasses and Beach Comber Bills sandals, and the weird way that my new California friends put the article “the” before highway numbers, as in “the 405”. I was shocked at all the ridiculously good-looking blond people with perfect smiles, and how autumn stayed warm and brightly sunny late into October and early November.

One of my roommates who ended up being a lifetime friend was Doug Perkins, an All-American wrestler from Reno, Nevada. He was what you imagined a wrestler from Nevada to be. He was solid, a veritable wall of muscle, and dipped Skoal tobacco from a small can that made a faded ring on the back pocket of his jeans. He had permed hair, photochromic eyeglasses, owned a black Stetson cowboy hat and spoke in an easy western drawl.

Doug and I would constantly argue about music and his record collection - he loved disco, and I hated it. He brought his Bee Gees albums to school, and I brought Talking Heads, Dylan and Little Feat. And we argued constantly about the terminal vowel sound of the state that he was from. To me it had always been Nev-AH-da, pronounced like Thurston Howell, III drawing out the middle syllable in classic Locust Valley lockjaw. He insisted it was Nev-A-da, like the “a” in the word “hat”. After all, he was from there, and I was an East Coast prep-school interloper.

Doug and a few of his friends called me a “preppy”, and as a prank cut off and held for ransom all the alligators on my Lacoste shirts and the tags from my clothes that were bought at “The Prep Shop” on Palmer Square in Princeton. It was funny, but it did ruin my shirts.

Later in October, I received another letter from John. He wrote about how he saw Allison, his high school girlfriend of camping tent fame during the Dartmouth trip, and he wrote that the visit was “alright”, but a “little tough”. He described his life as “complicated”. He asked me,

“How are your roomies, attitudes, courses (mundane, I know), sexual relations (mine are confusing) testicles, etc.”

Testicles?? I didn’t get it. I literally had no idea what he was talking about. Though I don’t remember our conversation, I telephoned him just after he wrote the letter but before he sent it, because he scribbled a note on the back.

“Jeff – Hello again. This is written after our talk on the phone…It was really good to hear your voice…”

I didn’t respond to his questions about my sex life, and I didn’t ask about his, and so the letters trailed off after that. It wasn’t until the beginning of his sophomore year that I saw him again on the bluff above New Haven as I was about to set out on my cross-country road trip. I was accompanied by three of my friends, Dan, Martha and Valerie who had flown back East to join me after I had spent the summer painting barns and farmhouses in the countryside around Kent, Connecticut. We planned to drive back to Stanford in my newly acquired 1974 British Racing Green Triumph TR-6 along with my Canadian friend Mike, another friend from freshman year, and my summer painting partner. Mike had spent the warm evenings after work restoring a 1970 Pontiac Le Mans convertible, and between the five of us we were stoked to see the country with the canvas tops down, cruising the open road.

I wished John and my conversation that day was more substantial and meaningful, but I distinctly remember thinking that I didn’t want to hear about all the complicated things he was going through. He was, like his letters, cryptic and indirect. So, I mostly talked about the adventure I was about to take with my California friends and how I was almost killed that summer by a giant pig, because I didn’t know that pigs were dangerous when I was painting on a ladder in its pig-sty, and partying in rural dive bars flirting with local girls, and working all summer on my car - to John’s utter boredom and disinterest.

Two years later, at the end of that summer of 1981, on the last day that I would ever see him, I met John at the house where he was living on Fell Street, in the middle of the Panhandle and the northern border of the Haight Ashbury district. We walked along the tall thin and deep townhouses that lined this small grassy strip of San Francisco.

These houses were once the crash-pads of the Grateful Dead and the Bohemian children of the summer of love. The area was one of the last holdouts in San Francisco of those times, and still hummed with the spirit of youthful abandon, drugs and free love, albeit a bit older and more faded. It retained the shabby appearance of colorful tie-dye banners hung from windows, recycled furniture lining the street, and the smell of weed and patchouli. But it was already turning into a double-decker bus tourist stop and an exaggerated stereotype of its former self.

I had brought Doug with me, and I could tell that John was disappointed that I didn’t come alone. If I am honest with myself, I asked Doug to come along so that whatever it was that John had to tell me was tempered by Doug’s persona. Maybe, I rationalized, that a good-old-boy from Nevada in the mix would keep whatever revelation John had in mind to a minimum level of drama? That was cowardly, and it was unfair to Doug, who was a far more complex person than that. I am ashamed to admit it, because by this point, I knew inside that John was gay, and I was uncomfortable with that.

My mother spent her entire life in the fashion industry in New York, surrounded by gay men. Her closest friends, when I was a child and still living in Long Island before my father died, were Karl and Burt, a gay couple who were often guests in our home. She told me when she heard that John was coming to San Francisco, that she always knew John was gay and couldn’t understand how I didn’t know that years ago as well. In fact, John had called my mother when he came to San Francisco for the summer to tell her about his decision to publicly come out, even before he planned to tell me.

I still don’t know why I didn’t understand this before. It’s hard to explain, but by blocking this understanding, I diminished the importance and essence of my best friend, all because I had an irrational fear of homosexuality. Perhaps I was worried like so many straight men, that the Kinsey scale is real – that we are all somewhere on the spectrum between gay and straight, and that can be disconcerting. In truth, I diminished both of my best friends, because Doug was also no stereotype. He was, and still is, one of the most sensitive, kind and welcoming individuals I have ever met. If anyone could have listened attentively and compassionately to John, it was Doug. The one who lacked emotional maturity, insight and empathy was me, and I will regret that forever.

As John and I walked towards the park, he told me about his college life since he last saw me, and about his work as a writer for Mother Jones, and about his decision to come to San Francisco to discover himself. He then talked excitedly about all the like-minded men he was meeting and the freedom to have new experiences, and the relief he felt. It was getting detailed and more and more personal. I took it all in, feeling distressed, awkward and even angry at John for making me feel this way. But it wasn’t John, it was me. I was afraid of this flood of information and my reaction to it and tried to think of ways to change the conversation as Doug walked a few paces behind us, listening, but not saying anything. Finally, exasperated, as if he was talking to an idiot, who was not getting it, John blurted out –

“Jeff, I am GAY!!”

I snapped back,

“John, I am happy too” … and grinned stupidly.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Doug wince. I have no memory of the rest of what was said on our walk, but I knew in that instant that I broke something in both of us and with those few poorly chosen, sarcastic words, our friendship.

On the way back to Palo Alto, I remember not talking much, but I do recall the feeling that I had done something irretrievably wrong. We drove my Triumph with the top down, out Oak Street and through SOMA, joining highway 101 heading South. The cold wet wall of fog abruptly gave way to a bright sunny afternoon once we passed Candlestick Park, then the airport and the familiar landmark of the It’s-It ice cream sandwich factory in Burlingame. The noise of the wind whipping my hair and the throaty roar of the in-line six-cylinder engine would have drowned out any conversation that Doug and I could have had. But he wasn’t saying anything. In my mind I could still see John’s crestfallen face and I felt the hot sting of shame and the tears in my eyes… and I keenly felt Doug’s quiet disappointment with me for the rest of the long car ride home.

Larkspur, CA

February, 26 2025

Post Script: This is from the Yale AIDS Memorial Project https://www.aidsmemorial.info/memorial/id=204/yale_aids_memorial_project.html

John Wallace was born in Princeton, New Jersey on July 22, 1960. From kindergarten through fifth grade, he attended the Littlebrook Elementary School; for middle and high school, he attended the Princeton Day School, where he starred in a number of theatrical productions. He enrolled at Yale in the fall of 1978 as a member of Berkeley College, graduating four years later with a degree in American Studies

An avid singer and actor, John was drawn to performance from a young age. At Yale, he became a member of the Spizzwinks, an a cappella group. After his junior year, he spent a transformative summer in San Francisco, where he came to embrace his homosexuality while working for Mother Jones. The following fall, he became a visible—and beloved—icon of gay identity on Yale’s campus, joining the LGBT Co-op and participating in a number of political actions, including the campaign to convince the University to expand its nondiscrimination policy. He also worked to unionize Yale secretaries.

After graduating, John moved to New York, where he began to freelance for magazines and TV. He worked as a writer for Channel 13, and penned articles for The Village Voice, GQ, and other publications.

In New York, he met and moved in with the playwright Lem Borden. The couple bought a house together in the Catskills.

John died of AIDS-related causes on February 28, 1990. He was 29 years old.

Incredible. We discussed your feelings about how you left things with John - but this essay is pure self awareness in addition to exceptional literature. I winced just like Doug...wow. To have carried this for years is a heavy load - but to have learned so much from it is the height of being human.

Thanks Irene. He was a special person and deserves to be remembered. I hope I captured his spirit.

The next installment in this series is almost done. Hoping to post it this weekend!